Statistics is often described as the “science of data,” but that definition is like describing a symphony as a “collection of notes.” In reality, statistics is the fundamental architecture of evidence. It is the bridge between the chaotic, overwhelming noise of raw information and the clear, actionable signals we use to make decisions. From the medication in your cabinet to the predictive text on your smartphone, statistical models are the invisible engines driving our modern world.

In this deep dive, we will explore the three pillars of statistical science: Descriptive Statistics, Inferential Statistics, and the Practical Application of these tools in our daily lives.

1. Descriptive Statistics: Mapping the Known World

Before we can predict the future or make generalizations, we must understand the “here and now.” Descriptive statistics provide the tools to summarize and visualize the data we currently have. Imagine you are looking at the test scores of 10,000 students. Without a way to condense that information, it is just a wall of numbers.

Measures of Central Tendency

These metrics help identify the “typical” or “middle” value in a dataset:

-

Mean: The arithmetic average. While commonly used, it is highly sensitive to “outliers”—single values that are much higher or lower than the rest.

-

Median: The middle value when data is sorted. This is the preferred measure for skewed data, such as household income, because a few billionaires won’t drag the median up the way they would the mean.

-

Mode: The value that appears most frequently, often used in categorical data like “most popular car color.”

Measures of Variability and Shape

Data isn’t just about the center; it’s about the spread. A narrow spread indicates consistency, while a wide spread suggests volatility.

-

Standard Deviation: This describes how much values cluster around the mean. In a “Normal Distribution” (the famous bell curve), roughly 68% of data falls within one standard deviation.

-

Skewness: This measures the asymmetry of the distribution. If the “tail” of the data stretches to the right, it is positively skewed.

2. Inferential Statistics: Predicting the Unknown

While descriptive statistics look backward at existing data, inferential statistics look forward. They allow us to take a small sample and make confident guesses about a much larger population. This is the logic that allows a poll of 1,000 people to represent the views of 300 million.

The Power of Hypothesis Testing

This is the scientific method in mathematical form. Researchers start with a Null Hypothesis ($H_0$)—the assumption that there is no effect—and use an Alternative Hypothesis ($H_1$) to suggest a change.

The $P$-value: This represents the probability that the observed results happened by pure chance. Generally, a $P$-value of less than 0.05 (5%) is considered “statistically significant,” meaning the result is likely real.

Correlation vs. Causation

One of the most famous rules in science is that correlation does not imply causation. Just because two variables move together—like ice cream sales and shark attacks—doesn’t mean one causes the other. Both are often influenced by a “lurking variable,” such as temperature.

3. Advanced Modeling: Regression and Probability

In the 21st century, we use statistics to find relationships between variables. Linear Regression allows us to predict the value of one variable based on another. For example, a real estate agent might use regression to predict a house’s price based on its square footage.

The Bayesian Revolution

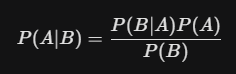

Unlike “Frequentist” statistics, which look only at data from the current experiment, Bayesian Statistics incorporate “prior knowledge.” It treats probability as a “degree of belief” that is updated as new evidence comes in. This is exactly how your email spam filter works—it has a prior belief about what spam looks like and updates that belief every time you mark a new email as “junk.”

4. Statistics in the Wild: Why It Matters to You

In 2026, we are awash in data, but data without statistics is just noise. The applications are everywhere:

-

Healthcare: Clinical trials use randomized control tests to prove a drug’s safety. Without statistical rigor, we wouldn’t know if a vaccine works or if its effects are coincidental.

-

Business: Companies use A/B Testing to see which version of a website leads to more sales.

-

Technology: Machine learning—the backbone of AI—is essentially “statistics on steroids.” Algorithms use statistical patterns to recognize your face, translate languages, and drive cars.